A young scientist discovered new algae and named it after Ostrava

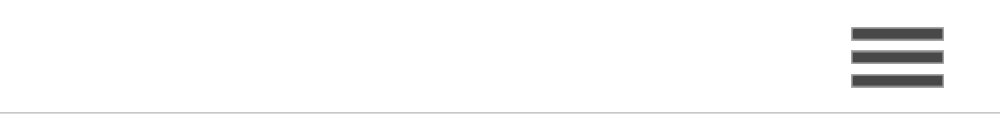

Ever since Dovilė Barcytė spotted algae under the microscope, she has been fascinated by the species. Moving from Lithuania to study at Charles University, she is now a postdoc in Marek Eliáš's team at the Faculty of Science. Soon after she got her feet under the lab's table, Dovilé managed to discover new algae species in Ostrava. Thanks to her, the city is now imprinted in the botanical encyclopedia, as the algae bears its name. Read more about Dovilė's journey to Ostrava and the research she does (not only) on the local slag heaps.

You greeted me in a good Czech. Where did you learn it?

I've been here for nine years. In the beginning, I was struggling with your mother tongue and after each lecture at Charles University, I ran home to translate every single word. Interestingly, I learned Czech in Germany during my Erasmus exchange. I had more time to study both German and Czech, and on top of that, one of the teachers came from Opava. Still, English is spoken among scientists much more so I feel way more confident speaking it than Czech.

It's been nine years since you landed in Czechia. Was it challenging to get used to living here?

Well, I come from a small town Šilale, where people know each other. Even though I'd studied in Vilnius before moving to Prague, the beginning wasn't always easy. Regardless of the language, I think Czech people are a bit more reserved than Lithuanians. You just need more time before letting a stranger close to you. Also, your sense of humour is specific and somewhat puzzling to me.

You started a new life. How did you get to the postdoc position at the Faculty of Science?

To be honest, the journey was quite simple. I was finishing doctoral studies at Charles University and looking for new opportunities in algae research. I'd met prof. Marek Eliáš on conferences before and I liked the research he does with his Ostrava-based team. I wrote him an e-mail, asking whether he, by any chance, needs an algae enthusiast in his team. Luckily, Marek was just looking for a new postdoc, so here I was, moving to Ostrava.

Do you miss Prague?

I don't miss the city at all. What I miss a little is the National Museum, where I was working for a while and met great colleagues. But I fell head over heels for Ostrava! Life seems easier here, and everything is close – I am at work in just a few minutes, a few minutes, do you understand it? What's more, people seem friendlier. The city is less anonymous.

What did you know about Ostrava before moving in?

I knew the basic facts; like that it's the third biggest city in Czechia, famous for its industrial past. But I also knew I was moving into a student-friendly city. I visited Ostrava a couple of times before, already noticing its authentic spirit and, in a way, a beauty. I was fascinated by the "metal giants" and slag heaps, which shape the landscape of the city.

Do you feel like a local now?

It's getting better with the time, but I still get lost now and then. I've been in Ostrava only since October 2019. :-). Besides that, everything is excellent! I enjoy working at the Faculty. It is a perfect place to start your career as a young scientist. The university is young, modern and open to initiatives and change where necessary. Both international students and employees are welcome here, and the university is ready to answer their needs.

How do you find working in Marek Eliáš's team?

First of all, I am grateful to work with a capacity like prof. Marek Eliáš. We share the same passion and enthusiasm for algal research. I learn from him every day and draw inspiration for my future research. He included me in exciting projects and gave me a lot of freedom and support to pursue my own ideas. What I find amazing is how the members of the professor's lab work together. We discuss problems and help each other, and there is no doubt we have a lot of fun while working.

Your field of research is a distribution, diversity and development of algae. How come that you've grown enthusiastic for algae?

Honestly, the moment I saw microalgae under the microscope for the first time I fell in love with it. I remember I was thinking, "Wow, I've never seen anything so beautiful in my life". That was the moment I knew I am an algal person. I started reading books and learning names of various algae, collecting samples and trying to identify them. I learned that morphologically similar algae can represent evolutionary distant phylogenetic lineages. However, at the same time, morphologically different algae can be closely related. This fact just blew my mind. That's why I became interested in algae diversification and speciation in particular. I am also engaged in a project focusing on bacterial endosymbionts and viruses inhabiting Eustigmatophyte algae cells.

How does the research look like in practice?

I collect soil or water samples and try to isolate targeted monoclonal algal strains. This process is quite long and tedious, but at the same time, exciting. I often notice cells I've never seen before, and I immediately want to know the organisms they represent. Interestingly, this led me to the discovery and description of multiple new species. I cultivate my isolates, observing them under light and transmission electron microscope (which allows visualisation of cell's ultrastructure). I isolate DNA and use PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) to amplify the targeted molecular marker. Most often, I use nuclear 18S and ITS2 rDNA and plastid rbcL to obtain nucleotide sequences for phylogenetic analyses. This method not only helps me to identify the organisms but also infer their phylogenetic relationships.

Since I moved to Marek Eliáš's lab, I am working with bigger data. We sequence organelle (plastid and chloroplast) genomes or transcriptomes of interesting microalgae from various taxonomic groups.

As a scientist, do you believe in systematic work or coincidence?

I believe in both. It is crucial to have clear aims and pursue them – that's quality science. However, exciting discoveries are also made by accident. If you love what you do, everything will just fall into place.

Do you have any idol in science?

As for the Czech scientists, I admire the work of Pavel Škaloud from the Department of Botany at Charles University. His knowledge of algae and the way he communicates it to his students is fantastic. I also respect my dear colleague and friend Ladislav Hodač, who works at the University of Göttingen in Germany. Ladislav not only taught me that science can be fun, but he also showed me how to believe in myself, and the research I do.

You collect your samples on Ostrava's slag heaps. Why there?

During my doctoral studies, I was focusing on microalgae living in extreme environments, mainly, acidic habitats (e.g., Soos Nature Reserve, Tinto River in Spain). Due to oxidation of sulphide minerals and subsequent formation of sulphuric acid, coal spoil heaps in Ostrava offer excellent environments for searching various acidophilic or acid-tolerant microorganisms.

That's what we learned with my colleagues in Prague with whom we discovered the thermoacidophilic red alga Galdieria sulphuraria on Heřmanice coal spoil heap. This alga needs a low pH (0.5–4) and high temperature (up to 56 °C) for survival. Therefore, it is mostly known from geothermal environments in Italy, Iceland or Yellowstone National Park in the USA. That's why it was fascinating to discover this microalga living secretly in Ostrava. I love slag heaps, especially the ones not recultivated – it's a real Eden of samples.

Galdieria sulfuraria is not the only discovery from Heřmanice slag heap, is it?

I've also isolated a green flagellate alga, which turned out to be closely related to Chlamydomonas chorostellata species, described in 1966 from acidic soil in New Zealand. Due to the complicated taxonomic history of the genus Chlamydomonas, we were able to establish a novel genus Ostravamonas, obviously referring to the name of Ostrava, where we re-discovered it. However, following the recultivation of the slag heap, the alga disappeared. This fact opens a debate, whether recultivation is a good thing, or we should protect the original character of slag heaps as they are a natural habitat to specific organisms. Anyway, when the works on the slag heap finish, the alga may return, we'll see. Still, we take into consideration other ways Ostravamonas got on the slag heap. Though transmission between large distances is not usual, we still flirt with the idea of transmission by air or birds from far away. However, the alga might have been brought here by a human too. We can imagine a traveller carrying it on his shoe from a holiday on the other side of the world.

Can you tell us more about Ostravamonas?

The genus Ostravamonas encompasses three species: O. chlorostellata known from New Zealand and Ostrava, inhabiting acidic terrestrial habitats; O. meslinii isolated from a ditch in France; and O. tenuiincisa of unknown origin.

Interestingly, several weeks after we published our paper describing Ostravamonas online, Japanese scientists released a study describing the same phylogenetic lineage and named the genus Paludistella. This shows how competitive science can be even in describing organisms. Since we were first to publish it, Ostravamonas should stay Ostravamonas.

What makes your discovery unique?

There are two reasons why the description of the novel genus Ostravamonas is important. First, it helps to better understand and organise the existing biodiversity within the green algal group Chloromonadinia. Second, it provides additional evidence that microalgae can spread over long distances and that they prefer specific environmental conditions (e.g., acidic habitats).

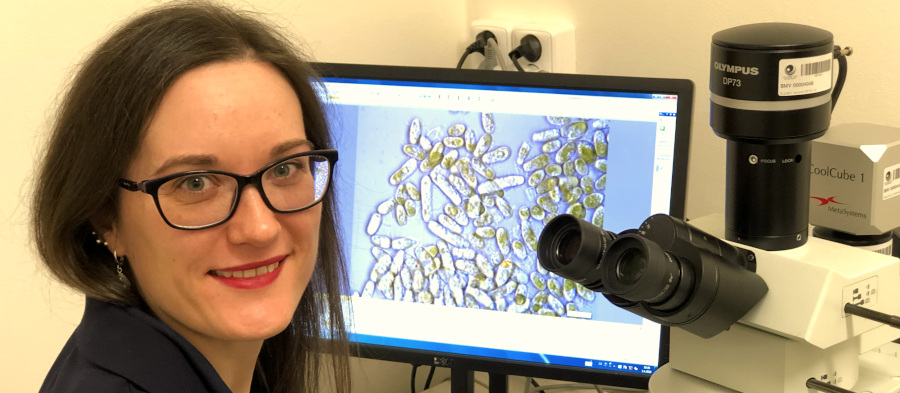

Under the microscope, what do Ostravamonas look like?

Ostravamonas is a unicellular green alga with two equal flagella and a papilla. Its chloroplast is cup-shaped with radial slits, and it contains a pyrenoid. The alga also has a red string-like stigma. Morphologically, it would be hard to distinguish it from other Choromonas- or Chlamydomonas-like microalgae. That's why we use molecular tools to identify such morphologically inconspicuous organisms.

In what way is your algae research useful?

It is important to realise that biogeography of microscopic algae is poorly known, with each new isolate contributing to the species' distribution. For example, by discovering Galdieria sulphuraria in Ostrava, we proved that the species is capable of spreading over Europe despite the common belief that ecophysiologically demanding alga cannot not survive long-distance travel.

What is more, the algal molecular diversity and phylogenetic relationships are far from being resolved. That's why the newly sequenced strains can fill phylogenetic gaps, resolve sister relationships, and provide a better explanation of speciation. That's the case of Ostravamonas falling within the ecologically well-structured phylogroup Chloromonadinia (Volvocales, Chlorophyta).

Finally, microalgae isolated from various extreme environments are attractive for biotechnological research since they can grow in a wide range of stressful conditions, and they produce unknown and highly valuable compounds.

Having discovered a new species, what are you up to now?

I am currently working on the little known genus Olisthodicus described already in 1937 from brackish waters of England. I use protein sequences of multiple plastid genes to elucidate its phylogenetic position within the Stramenopiles (ochrophytes). Our data show that the genus Olisthodicus has unexpected characteristics, representing a new class of these algae.

Is there any dream place to study algae?

I had several sampling trips in Svalbard, and I fell in love with the place. I would like to come back to the Arctic. Next, I would like to do biodiversity research in Antarctica, as it is a promising place to find a lot of unique organisms.

Finally, what makes you continue in your research?

Well, I truly love what I do.

Zveřejněno / aktualizováno: 09. 04. 2020